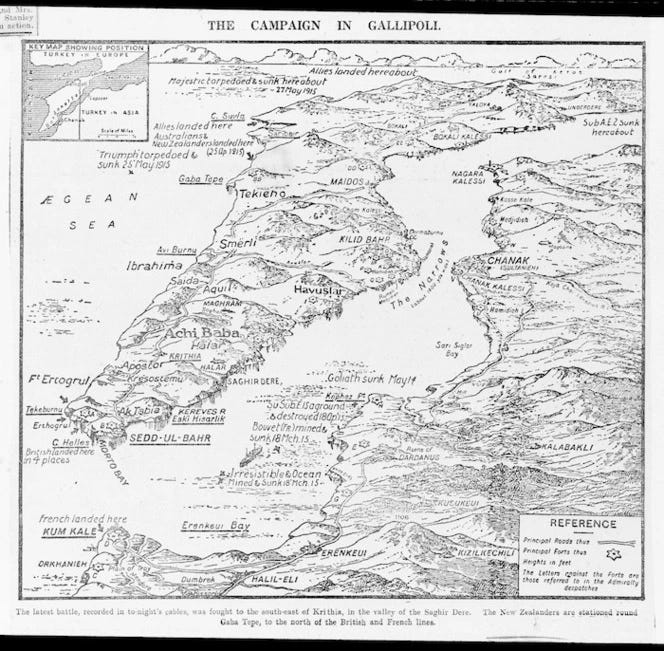

Alexander Craig Aitken was born in Dunedin, New Zealand, on 1st April 1895, one of that doomed generation which came of age at the height of the first world war. He joined the New Zealand Expeditionary Force in April 1915 and was then sent via Egypt to Gallipoli. It was en route to Gallipoli that he acquired a violin which he carried with him throughout the war and would often play to entertain his fellow soldiers in the trenches. After a brutal introduction to modern attrition warfare against the armies of Kamal Ataturk, his unit was transferred to the Somme. A highly capable soldier, Aitken won a commission in August 1916 but was badly wounded the following month, taken away to London for medical treatment and then invalided out of the army. This allowed him to leave for New Zealand in 1917 to put his life back together, before returning to the United Kingdom with a post-graduate scholarship, studying in Edinburgh under the great analyst E T Whittaker. He would succeed Whittaker as Chair of the Mathematics Department and made wide-ranging contributions to statistics, numerical analysis and linear algebra. Econometricians familiar with the history of regression analysis will most likely associate his name with the Generalised Least Squares method for parameter estimation which he first described in an important paper in 1935.

Outside of the university, he achieved minor celebrity for his astonishing capabilities as a mental calculator. He could square and take the roots of large numbers almost instantly, factorise others and identify primes with unerring accuracy. His facility with numbers was so extraordinary that he was studied by the psychologist I M L Hunter, who published a report on Aitken in the British Journal of Psychology in 1954. Aitken also had near perfect recall and could recite all 707 digits from Shanks’ calculation of π with complete fluency. He even made it on to the BBC; below is an excerpt from his interview with Fyfe Robertson in 1962:

His unusual mental faculties would help him solve problems requiring complex computations that other mathematicians found practically impregnable before the introduction of electronic calculators. They were also helpful during the war. When the commander of his unit lost the Platoon roll in Flanders, he turned to Aitken to reconstruct the entire ledger from memory:

'I became aware of a conversation in low tones going on somewhere behind me, apparently between Captain Hargest and Mr Rae, and perhaps occasionally someone else - but I am not sure of this. However that may be, something was missing; a roll-book; the roll-book of Platoon 10, my old Platoon. Urgently required, it seemed; Battalion had rung up, requesting a list of the night's casualties and a full state of the Platoon. Apparently surnames were available, but the book was nowhere to be found. This being suddenly clear, I had no difficulty, having a well-trained memory now brought by stress into a condition almost of hypermnesia, in bringing the lost roll-book before me, almost, as it were, floating […] speaking from the matting I offered to dictate the details; full name, regimental number, and the rest; they were taken down, by whom, I know not.'

A C Aitken, Gallipoli to the Somme: Recollections of a New Zealand Infantryman, Auckland University Press 2018, p. 105

However, like the character in Borges' short story 'Funes the Memorious', Aitken's memory was also a source of terrible mental anguish. In particular, he suffered from periodic bouts of depression as he struggled to suppress memories from the war. As an exercise in therapy he wrote down his recollections which were eventually collected in a magnificent short memoir, Gallipoli to the Somme (1963), from which the above quotation is taken. Despite being the only literary work Aitken published in his lifetime the book was so well received that it won him a fellowship with the Royal Society of Literature.

Gallipoli to the Somme is a war memoir of the first rank, which deserves a place next to Blunden's Undertones of War, Graves's Goodbye to all That and Junger's In Stahlgewittern. Like those books it is both an important historical document and a literary masterpiece. The hallmark of Aitken's style is his clarity, which has a peculiar luminous quality unlike anything I have come across in the wider war literature. It often feels as though you can see what you are reading with almost stereoscopic vividness, such is the precision with which language and experience are calibrated by Aitken. Most likely this has something to do with his prodigious memory but I would want to avoid any crude reductionism here. He was searching for, and ultimately found, a language that could meet the hard demands of fidelity he set for himself, both to the horrors of the war and to the bravery of his fellow soldiers. 'Vagueness', he remarks in one of the early chapters, is a 'refuge' and an 'emollient' for the traumatised infantryman. It is something that he refuses throughout the book, always preferring hard detail over the 'gloss' of abstractions. The total effect is a style that often rises to the level of poetry, albeit poetry of a very severe beauty:

'[…] I stooped under the water-proof door sheet and stood for a minute waiting for the diffused light to show me the way to my slot-bed. The contrast was extreme; inside, the warmth and comradeship of men far from home but remembering it and forgetting the war for a brief hour; outside, the ink-black valley, the hill just visible in the frosty starlight, the desultory rifle shots […] I began my walk, but stopped at half-way, conscious of danger, as of a rattlesnake. A string of hisses, rapid and even as semiquavers, sounded just in front of my knee, accompanied by soft thuds somewhere to the right; machine gun bullets at the end of a very long trajectory. A forward swing of the arm, and the violin case would have been perforated […] For a while I lay awake, shaken by this escape from the arrow that flieth by night, and by the gossamer thinness of the partition between life and death; but I slept none the less soundly'

A C Aitken, Gallipoli to the Somme: Recollections of a New Zealand Infantryman, Auckland University Press 2018, p. 38

He writes elsewhere in the book, concerning their training in the new system of bayonet fighting, that to describe the ordered savagery of the instruction was to 'indict civilisation'. The book contains many such indictments. But the most memorable passages all come when what Aitken calls the 'conditioned callousness' of the trenches vanishes, and the 'real world' of justice, mercy and peace overcomes the phantasy 'world of arbitrary violence and random death'. A striking example of this comes as his unit, now in Flanders, is transferred to the town of St Omer on a route that goes through a number of small Flemish villages. Aitken writes:

'Slight incidents engrave themselves on the mind when great events are forgotten, and impressions of this journey stand out for me with peculiar colour; chief of all a level crossing between St Omer and Audruicq, where a dog-cart carrying two girls was waiting for the train to pass. They had distinction, and one was beautiful; and I had the vision of a lost former world, containing poetry and the music of Chopin, to which mud and dust and khaki were strangers and unknown; the incident of a moment, a spark in the night at once extinguished and never forgotten. So, too, I remember the train slowing down a little before Audruicq to pass a village called Ruminghem, and the kindly old people who waved to us from their gates in the evening. The light of eternity shone on them in the level western beams; mortality did not touch them, they were the fixed we the transitory: they must be dead these many years, but to me they will always be as those undying simplicities in paintings by old Dutch masters - a woman, it may be, drawing water from a well in a court, or a girl reading a letter by a window'

A C Aitken, Gallipoli to the Somme: Recollections of a New Zealand Infantryman, Auckland University Press 2018, p. 113

There are many other treasures like this in the book and I would not want to deprive you of the opportunity to discover them for yourselves. I will only share one more , which also has a peculiar historical value. It comes just before the ill-fated raid conducted by his 4th Otagos at Armentiers in the summer of 1916. The evening prior to the engagement Aitken's men had taken up forward positions close enough to the German lines to be within earshot of the opposing infantry:

'The night before the raid, the 12th July, was heavy and still, with the brooding feeling, in my mind at least, that minenwerfer bombardment might suddenly start on the right. At dusk a flute was heard playing in the German trenches; unfamiliar airs, German folk-songs, with the same affecting turns and cadences as occur in Schubert's Morgengruß from the song cycle Die schöne Müllerin. This was melting while it lasted; but with true German gallows humour the unseen flautist, knowing that we must be listening, modulated into a travesty of the Dead March in Saul, bizarre and truly macabre. To me it seemed to say, 'For you tomorrow night, Kameraden!'.'

A C Aitken, Gallipoli to the Somme: Recollections of a New Zealand Infantryman, Auckland University Press 2018, p. 96

Apart from its sheer surreality, almost absurdity, there is a profound pathos to this sequence. This act of macabre humour was only possible because the German infantryman with his flute, and the Anzac mathematician lying in the nearby trench, shared the same high European culture, one which placed a particular value on the humanising effect of great art, including the music of Schubert and Handel (the latter a perfect mixture of English and German sensibilities). The next day they would wake up and be swept back into the current of a war that would ultimately destroy that culture, and millions of men that were brought up to love what it valued. That world is now vanished and its ruins are everywhere around us. If we cannot rebuild it then at the very least we should endeavour to remember it.

Alexander Craig Aitken, 1896-1967, requiescat in pace