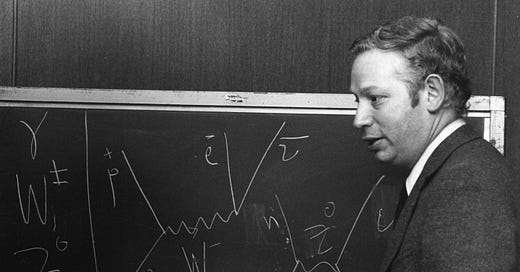

At the time of his death a few years ago, Steven Weinberg was widely recognised as one of the most influential physicists of the second half of the twentieth century. His theoretical work on the electromagnetic and weak interactions had been pivotal in the creation of the 'Standard Model' of particle physics. In this way his name was inscribed on what is often called the 'most successful scientific theory' of all time. This is the greatest monument a scientist could hope for, followed closely by a Nobel prize, which he won for the same work in 1979. He was also a highly effective science populariser, writing a number of books for the lay reader, and an indefatigable essayist (two volumes of his essays were published by Harvard's Belknap Press before he died).

One of those books, Dreams of a Final Theory (1992), contains an interesting chapter entitled 'Against Philosophy' in which Weinberg makes his case for the absolute irrelevance of philosophy for science. It is a view that has become increasingly popular in scientific circles. Indeed, it seems to have risen to the level of a self-evident truth for some. This may explain why Weinberg does not really offer any arguments for his position in Dreams. He opens the chapter with the following metaphor:

The value today of philosophy to physics seems to me to be something like the value of early nation-states to their peoples. It is only a small exaggeration to say that, until the introduction of the post office, the chief service of nation-states was to protect their peoples from other nation-states. The insights of philosophers have occasionally benefited physicists, but generally in a negative fashion—by protecting them from the preconceptions of other philosophers.

Steven Weinberg, Dreams of a Final Theory: The Search for the Fundamental Laws of Nature, (Vintage, 1993)

This is equally wrong about nation-states and philosophy. Indeed, the comparison is so defective that I wonder whether it is part of a subtle rhetorical strategy, showing that Weinberg's position is so obvious that is can be defended with the laziest metaphor-making. That said, it does put across that position quite clearly. According to Weinberg, philosophy can do two things for the scientist. It can introduce errors and it can take those errors away. At best, philosophy is then a helpful solvent for the bits of philosophical junk that science has picked up over time. At worst, it can contribute to the proliferation of such junk. Apart from that it can offer a 'pleasing gloss' on the history of science and its discoveries and so provide the working scientist with an enjoyable hobby. The main point of the chapter is to issue the following challenge: find me a scientist who has ever been helped by philosophy:

I know how philosophers feel about attempts by scientists at amateur philosophy. But I do not aim here to play the role of a philosopher, but rather that of a specimen, an unregenerate working scientist who finds no help in professional philosophy. I am not alone in this; I know of no one who has participated actively in the advance of physics in the post-war period whose research has been significantly helped by the work of philosophers.

Steven Weinberg, Dreams of a Final Theory: The Search for the Fundamental Laws of Nature, (Vintage, 1993)

There are many things one can say about this. First, it demonstrates the 'sticky' nature of philosophy. Put simply, you find yourself doing philosophy even when you try to denounce it. Weinberg may not have aimed to 'play the role of a philosopher', but he ends up doing it in spite of himself, and doing it poorly (so much the worse for philosophy, you may say). But the most interesting bit about this quotation is the qualifying phrase 'post-war period' in the third sentence. Weinberg had to include this proviso because he was an honest person and knew that the pre-war period in mathematics and physics, and its immediate aftermath, were dominated by scientists who were either keen students of philosophy or philosophers in their own right. Here are some other 'specimens' Weinberg could have presented for our consideration: Albert Einstein, Erwin Schrodinger (a philosopher), Wolfgang Pauli, Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg (also a philosopher), De Broglie, Kurt Gödel (a first rate philosopher), Herman Weyl (a first rate philosopher), Alexander Friedmann, and so on and so on.

I am not a physicist but do have some training in economics, which is another scientific field that Weinberg mentions en passant. I will leave it for physicists and scientifically-inclined philosophers to adjudicate on what we can call the 'weak Weinberg hypothesis' - that philosophy is utterly useless for physics. Though there is some irony in the fact that, since Weinberg published Dreams, the debate over the prospects for a 'final theory' have become increasingly philosophical. For example, the endless fight over the validity of string theory, at least for the outsider, seems to be centred on questions about the ontological status of the objects represented by its complicated mathematical formalism. I am more interested in the 'strong Weinberg hypothesis' that philosophy is an impediment to all science, including the social sciences, which seems to me catastrophically wrong. And yet I think most economists would probably agree with Weinberg.

I want to conscript another superb specimen of the 'scientist-philosopher', mathematician Gian Carlo Rota, to assist me in my rebuttal. Rota is by no means the most obvious person to call up to the dock to defend philosophy. In some of his polemical essays he is far more critical than even Weinberg. Take for example, his excellent essay "The Pernicious Influence of Mathematics Upon Philosophy" (Synthese, 1991) published elsewhere under the title "Mathematics and Philosophy: The History of a Misunderstanding":

'Science deals with facts. Whatever it is that traditional philosophy deals with, it is not facts in the scientific sense. Therefore, traditional philosophy is worthless.

This syllogism, wrong on several counts, is predicated on the assumption that no statement is of any value, unless it is a statement of fact. Instead of realizing the absurdity of this assumption, philosophers have swallowed it, hook, line and sinker, and have busied themselves in making their living on facts.

But previous philosophers had never been equipped to deal directly with facts, nor had they ever considered facts to be any of their business. Nobody turns to philosophy to learn facts. Facts are the domain of science, not of philosophy. And so a new slogan had to be coined: philosophy should be dealing with facts.

This "should" comes at the end of a long line of other "should's". Philosophy should be precise, it should follow the rules of mathematical logic, it should define its terms carefully, it should ignore the lessons of the past, it should be successful at solving its problems, it should produce definitive solutions.

Pigs should fly, as the old saying goes'

Gian-Carlo Rota, “The Pernicious Influence of Mathematics upon Philosophy." Synthese, vol. 88, no. 2, 1991, pp. 165–78.

Even Weinberg would have winced at these asperities. Rota goes on to argue that philosophy is indeed useless as long as it apes the methods of mathematics. He contrasts the pseudo-mathematical philosophy which he attacks with such force in the paragraph above with traditional 'speculative' philosophy which is principally concerned with 'how to look at the world'. In its speculative mode philosophy has the salutary effect of 'correcting and redirecting our thinking' by surfacing our 'glaring prejudices' through a sort of free play of the mind with its conceptual equipment. It does not add to the stock of facts but makes us think about the myriad configurations we could give to those same facts under different assumptions. Further, while the assertions of philosophy are less reliable than those of mathematics they 'run deeper into the roots of our existence'. This is where the relevance of philosophy to economics and related social sciences comes in. I don't think anyone has ever claimed that economic questions run down 'into the roots of our existence'. However economic decisions ultimately do run up from the roots of our existence, and much of the difficulty in economics comes from the fact that its objects are not mindless particles but human beings who are concerned with issues of value. This makes economics a source of 'awesome complexities', as Rota says of psychology and the biological sciences.

'The reality we live in is constituted by myriad contradictions, which traditional philosophy has taken pains to describe with courageous realism. But contradiction cannot be confronted by minds who have put their salvation in axiomatics. The real world is filled with absences, with absurdities, with abnormalities, with aberrances, with abominations, with abuses, with Abgrund'

Gian-Carlo Rota, “The Pernicious Influence of Mathematics upon Philosophy." Synthese, vol. 88, no. 2, 1991, pp. 165–78.

Philosophy then should be there to rescue the economist from the consequences of the original sin of that science - thinking that by axiomatics we can lift ourselves out of the Abgrund.

Any discipline that needs the science acollade is not Truly science.