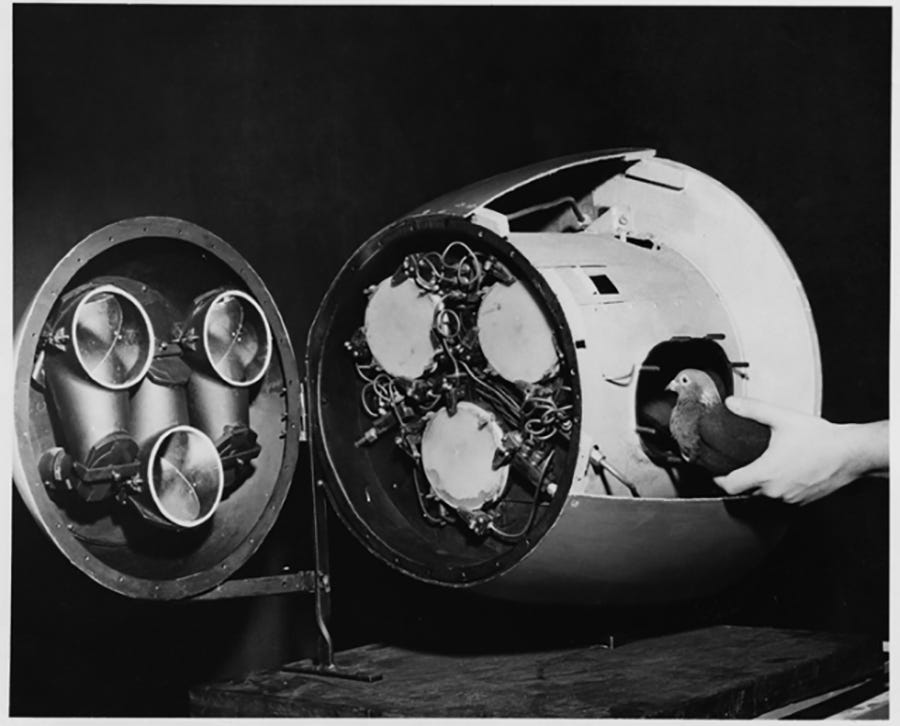

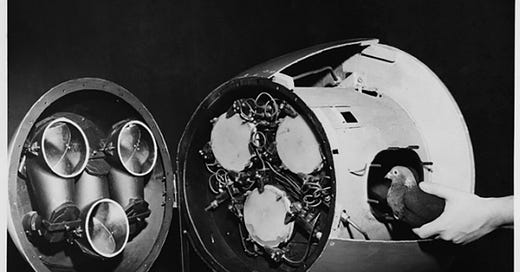

I have been re-reading Hannah Arendt's The Human Condition and find it to be a very different sort of book when viewed from the perspective of the philosophy of economics. Arendt has little to say about economics directly though there are a handful of scattered references to it in the index. What is interesting about these largely disconnected passages is that most of them overlap in the book with Arendt's broader critique of 'behaviourism'. Behaviourism can mean many things. Following the useful article in the Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, a good working definition is the doctrine that all 'behaviour can be described and explained without making ultimate reference to mental events'. It also refers to a powerful historical movement in the field of psychology that had its heyday in the middle of the last century, around the time Arendt wrote The Human Condition. Headed by the strange figure of B F Skinner, the behaviourist school was interested in systematically removing the language of 'inner life’ from psychology and replacing it with descriptions of externally observable behaviour. What could not be represented using such ‘external’ descriptions was jettisoned as unreal. To this end Skinner, among other things, taught pigeons to play ping pong as well as guide missiles. He also wrote a Utopian novel about a future behaviourist idyll - Walden Two - a hilarious title if you are familiar with Henry David Thoreau's original Walden.

Under the constraints imposed by the behaviourists, animal and human behaviour is reducible to some function of four concepts: external stimuli, physical response, learning history and reinforcement (sound familiar?). This was a severe and sparse language but held out one great promise - that it could be turned into mathematical symbols, and so brought under the sway of the all-conquering empirico-deductive method of the hard sciences. In particular, it opened the pathway for the use of then relatively new statistical techniques in psychology.

This brings us back to Arendt, who writes this about the behaviourist tendencies in economics:

'The laws of statistics are valid only where large numbers or long periods are involved, and acts or events can statistically appear only as deviations or fluctuations. The justification of statistics is that deeds and events are occurrences in everyday life and in history. Yet the meaningfulness of everyday relationships is disclosed not in everyday life but in rare deeds, just as the significance of a historical period shows itself only in the few events that illuminate it. The application of the law of large numbers and long periods to politics or history signifies nothing less than the wilful obliteration of their very subject matter, and it is a hopeless enterprise to search for meaning in politics or significance in history when everything that is not everyday behaviour or automatic trends has been ruled out as immaterial […] statistical uniformity is by no means a harmless scientific ideal; it is the no longer secret political ideal of a society which, entirely submerged in the routine of everyday living, is at peace with the scientific outlook inherent in its very existence'.

Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, The University of Chicago Press (1958), p. 42

That last line, incidentally, is a perfect description of the social arrangements of Skinner's utopia.

Arendt's point is probably put too bluntly. It displays some of her prejudices against the application of numerical methods outside of the traditional 'hard sciences', and also suffers slightly from being taken out of its proper context. There are really two separate arguments that run together in this paragraph. The first is on the usefulness of statistics for social phenomena, where Arendt argues that human action is special - it is free, spontaneous and so can be the source of real novelty. This injection of novelty comes from individuals but can have system-wide effects. This is the opposite of, for example, a passage I recently found in Pareto, who is happy to say that for the purposes of economic analysis 'the individual may disappear; we do not need him any longer in order to determine economic equilibrium'. So part of her argument is against the idea that we can ever let 'the individual disappear' and still give a reasonable explanation of social phenomena. Her second argument is that we can envisage a set of social arrangements that would minimise human freedom to such an extent her first argument becomes irrelevant.

The only economist I can think of who would agree wholeheartedly with Arendt is the great (but sadly undervalued) G L S Shackle. A student of Hayek at the LSE who eventually defected to the Keynesians, though he was never very comfortable as a member of any school, Shackle was a ferocious critic of the same tendency in economic theories to 'obliterate' the human person that Arendt identified with the behaviourists. In a very interesting little essay 'The Unity of European Economic Thought' (1961) Shackle plays with the idea of inviting the luminaries of contemporary economics to a conference and putting some basic philosophical questions to them:

'How do you conceive the source of human action? Is it a mechanical response to objective circumstances, or to circumstances as they are known to the acting subject? What if his knowledge of them is incomplete or false, and indeed how can it be other? What precisely is the role of knowledge, with its inevitable deficiencies differing from person to person, in allowing the circumstances to elicit action from the individual? Or is action in part spontaneous, creative, uncaused; perhaps constrained but not determined by the subject's knowledge? How in this case can we construct a predictive science of the genesis of events? How are human motives to be summarized?

G L S Shackle, 'The Unity of European Economic Thought' in The Nature of Economic Thought: Selected Papers 1955-1964, Cambridge University Press (2010), p.5

In other words, to what extent are your assumptions behaviourist? Musing on this battery of questions, Shackle continues:

'…we are reaching down to the bedrock problem concerning the human condition, the choice of assumption between determinism and non-determinism, a problem which I suspect economists of answering, by implication, in various ways according to the convenience of the argument in hand. Some would say these waters are too deep. I can only ask whether, if we wish to make decision an originative act giving its own unpremeditated twist to the spinning yarn of history, can we then consistently claim a predictive purpose for economics?'

G L S Shackle, 'The Unity of European Economic Thought' in The Nature of Economic Thought: Selected Papers 1955-1964, Cambridge University Press (2010), p.6

Shackle's later work – in particular his Epistemics & Economics: A Critique of Economic Doctrines and his ideas about ‘inertial dynamics’ - can be interpreted as a way of reconciling economics with a fuller conception of the human person than that provided by Skinner and Co.

So that's Arendt (the philosopher) and Shackle (the economist) – what about Arthur Koestler (the novelist)? Well Koestler does what a writer does best and summarises the Arendtian-Shackelian position in a couple of pregnant sentences in the astonishing chapter he contributed to The God that Failed: Six Studies in Communism (1950):

'The lesson taught by this type of experience, when put into words, always appears under the dowdy guise of perennial commonplaces: that man is a reality, mankind an abstraction; that men cannot be treated as units in operations of political arithmetic because they behave like the symbols for zero and the infinite, which dislocate all mathematical operations…'

Arthur Koestler in The God that Failed: Six Studies of Communism, Hammish Hamilton (1950), p.76

My impression is that mid-century psychology and psychiatry were pretty creepy.

Great Koestler quote. The math analogy reminds me of how Rubashov, the old Communist cadre in Darkness at Noon, refers to the pronoun "I" as "the grammatical fiction."