Cresting the hill Martha saw the shattered bones of the town spread out under livid clouds. A single building stood at the centre of the ancient carnage. Dust lay sifted on its blasted masonry, undisturbed by wind or life. She was safe, for now.

The decision had been made to leave that morning and this was the last chance to explore the ruins. Storms were coming from the south and with them a vast plume of toxic dust that was expected to make fall in the next few days. Hard experience had taught her little clan that tarrying while the big dusts moved invariably led to disaster. And so, as they had done many times before, they were preparing to migrate across the wasteland.

Martha walked along the main street toward the building, her heavy boots leaving hard-ridged imprints with each step. She long ago stopped worrying about finding other people in ruined places and nonchalantly circled the structure looking for an entrance, which was now just a large rectangular hollow in the wall. Ambling over the threshold she started to scan the interior for anything that could be carried with them. By now she felt as though she knew all the forms ash could take, but something was strange here. It was folded and curled in sheet-like layers, hard and crystalline. These small sheaves were everywhere, some perfectly cylindrical, others breaking down into piles of black sand. It was beautiful in the way she imagined a coral cave was, all glittering with sea-rime.

Then she saw it and immediately knew where she was. Lying at the base of a column was the burned cover of a red and black book, the only one that had not been turned into brittle ash-foils when the heat-wave struck the library. She moved toward the book and, sinking to her knees, inspected it. Mouthing out the letters as she had learnt them from the few texts passed on by the first survivors, she spelled out the title: "The Better Angels of our…”. The last word had been scorched through, presumably by a fallen ember, but below it she could clearly discern a name, ‘Steven Pinker’.

Carefully separating the cover from the next page her heart dropped. There was only one legible line, the rest had been seemingly carbonised. ‘This book is about what may be the most important thing that has ever happened in human history’. Her mind was set into furious motion by these three new facts - angels, Pinker, the most important thing. Could it be true? Were there angels? Had they really broken into history? If there were angels they must still be here, lingering somewhere above our misery, waiting to save the human wreckage that scurried over this blighted planet. Perhaps Pinker had met with them and that was the most important thing that has ever happened. Something also was happening inside her that she could not describe. It was as though a seemingly dead ember deep within her heart had been kindled into flames.

She looked to place the book on the floor but it slipped from her hands and split in half on the hard ground. Fresh leaves full of text sprung out of the black casement, revealing to Martha that the book had somehow survived partially intact. Blood throbbed in her temples as she lowered herself down on her arms, lying almost directly over the curved pages. She started to read. She read and read, desperately, whole passages at a gulp. Some she said aloud, as if to make them more real:

As one becomes aware of the decline of violence, the world begins to look different. The past seems less innocent; the present less sinister. One starts to appreciate the small gifts of coexistence that would have seemed utopian to our ancestors: the interracial family playing in the park, the comedian who lands a zinger on the commander in chief, the countries that quietly back away from a crisis instead of escalating to war.

She went on eyeballing the letters:

… Man's inhumanity to man has long been a subject for moralization. With the knowledge that something has driven it down, we can also treat it as a matter of cause and effect. Instead of asking. "Why is there war?" we might ask "Why is there peace?" We can obsess not just over what we have been doing wrong but also over what we have been doing right. Because we have been doing something right, and it would be good to know what exactly it is.

Martha looked outside at a clearing in the rubble which might have been a park before the town was destroyed. She imagined the family from the book passing by in languid procession, each figure lovingly framed in her mind with a nimbus of light. And then she thought about Pinker’s “causes of peace” and how they had conspired to annihilate that shining scene - reason designing the bombs, trade putting them together and the leviathans in their mad logic launching them up like fireworks in the night. The past did seem less innocent; it seemed guilty, only in the way a drunkard is guilty when he takes the poison that sends him blind into some egregious calamity.

And where were the angels? Pinker did not believe in them. The people who spoke with angels were the enemies of peace, he said, sadists, extortionists, worshippers of death. Pinker’s angels were men, bits of men - the ‘better angels of our nature’ - a bitter phrase that lodged in her throat when she tried to pronounce it.

Slowly, inexorably, the ember in her heart was extinguished. Its hidden warmth, which sustained her through the terrors of the wasteland, had gone and she knew it now for the first time in its absence. With it went also her fear, that twin-born thing which had shadowed every day of her short life. Martha laughed. She thought about the others, who would be departing soon, abiding by the rule that had kept them alive, that stragglers should be left behind if the dusts were in the air.

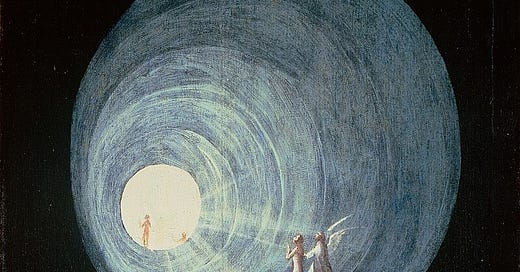

Lying down in the desolated library she closed her eyes and began to sleep. She saw the great escalator of reason and on it men being conveyed into a vast, shimmering conflagration. She saw a man separated from the rest, lank ringlets of hair dripping over his face, frantically tracing concentric circles in the dust, wider, wider, wider, his fingers full of blood. Angels flowed across her vision, golden and massive, scudding through the air and picking the men off their feet, then carrying them away into a point of light where they vanished for a time.

The first whispers of the coming wind mingled with those dreams, but if before they were full of foreboding, now they spoke of mercy, reconciliation. ‘Pinker, Pinker… Pinker’, she intoned the words solemnly, wistfully, and then smiled before yielding herself up to the golden hands in the sky.

Tremendous! The only possible levity in man made apocalypse is how utterly ridiculous it makes Pinker look. Almost worth a go. Perhaps there is even salvation of sorts therein (as you suggest). If only Cormack McCarthy's characters had read Pinker... The Road might have afforded some maddening comedy that perhaps Balzac also saw.

I'm reminded of the final line of Robert Browning's "Love Among the Ruins": "Love is best." I pray that the angels of peace will shed their blessings not just on Martha, but on all who strive and suffer.