Luzin, Florensky and the Trials of Materialism

A story from the dark night of Soviet religious suppression

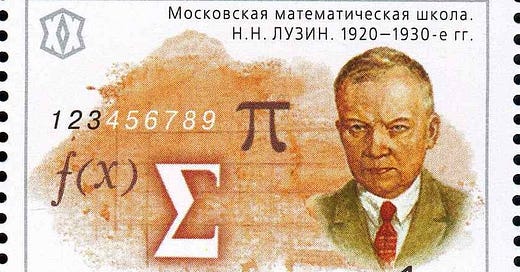

This Friday marks the 75th anniversary of the death of the Russian mathematician Nikolai Nikolayevich Luzin (1883-1950). Luzin is best known today, if he is known at all, for two reasons: first, for framing the Luzin Conjecture which, after its proof in 1966, is now more commonly referred to as Carleson's Theorem; second, for his role at the centre of the 1936 'Luzin Affair', a political conspiracy that tore apart the Russian mathematical community and almost cost Luzin his life.

Luzin rose to prominence as the founder of the Moscow School of the theory of functions of a real variable, which became the locus for an explosion of mathematical creativity in Russia in the first half of the 20th century. The charter and foundation of this school was Luzin's pathbreaking monograph on Integral and Trigonometric Series, published in 1916. His interest in what was then a nascent area of mathematical analysis grew out of a period of study in Paris, where he came into contact with a number of leading French mathematicians, including Henri Lebesgue, Emile Borel, and Emile Picard. Lebesgue later wrote the foreword to Luzin's Lecons sur les ensembles analytiques et leurs applications in 1930. The extent to which his own investigations into the groundwork of analysis were influenced by 'reactionary' French intellectual currents would in part decide the outcome of the allegations that were later brought against him in 1936.

Luzin returned to Russia in 1914 and by the time the county re-emerged from civil war as the USSR, he was the leader of a circle of young mathematicians half-jokingly known as 'Luzitania'. Members included, Pavel Alexandrov, Pavel Urysohn, Vyacheslaw Stepanov (the 'three Pauls of Luzitania'), the Pole Wacław Sierpiński and Andrey Kolmogorov. Luzin was duly elected as a corresponding member of the USSR Academy of Sciences in 1927. However the first sign of the coming storm arrived when his teacher and mentor Dmitri Egorov was targeted by the authorities for his 'reactionary' religious views. The persecution of Egorov can be traced back to the sinister figure of Ernest Kolman, a fanatical Bolshevik mathematician of dubious academic merits, who later became head of the scientific section of the Moscow Party Committee. Egorov was arrested, imprisoned and died, most likely as the result of a hunger strike, in 1931.

With Egorov eliminated, Kolman took aim at Luzin. 1936 saw the publication of an anonymous Pravda article containing a litany of denunciations - Luzin was a plagiarist, the importer of fascist ideology from the continent, a crypto-tsarist and religious obscurantist like Egorov, and so 'an enemy in a Soviet mask'. The Presidium of the Academy of Sciences were instructed to set up a special commission to determine the validity of these accusations. What followed was an inquisition, which over a series of increasingly hysterical sessions, worked up a comprehensive indictment of Luzin, both as scientist and pedagogue. Many of his students abandoned him and some became informants for the authorities, while others used the opportunity to air longstanding grievances. Luckily the first report from the commission reached Stalin in one of his less blood-thirsty moods, and the decision was made to deprive Luzin of his university post, but not to arrest him.

The 'Luzin Affair' is documented in a wonderful book edited by Sergei Demidov and Boris Levshin, which includes reconstructed stenographic records of the anti-Luzin committee meetings. However, there is a less well-known episode in Luzin's life, which forms an important aspect of the wider context of the 'Affair'. Over the five year period between his graduation and the conclusion of his studies in Europe, Luzin underwent a profound spiritual crisis, which drew him into the same 'reactionary' religious circles that would later make him a target for Kolman. What we know about this period of Luzin's life comes from his correspondence with the theologian and priest Pavel Florensky, who had befriended Luzin at the Moscow University faculty of Mathematics and Physics. A letter dated 01 May 1906 from Luzin to Florensky gives a picture of his psychological turmoil:

I received your letter three weeks ago, and only now am I able (perhaps) to reply… Life is too depressing for me, sometimes agonizingly depressing. I am left with nothing, no solid worldview; I am unable to find a solution to the problem of life. My self-image is so frequently changing that life has become pure torment […] It is horrible, horrible, infinitely horrible to feel yourself surrounded by egoism, nothing but unrelieved egoism.... There is such a lack of respect for people and even life itself. . . . If I were sure that in fact there is not and cannot be any absolute respect in the world for the soul of another, I would kill myself immediately. I cannot imagine living without that hope…

Luzin goes on to explain how the 'problem of life' had suddenly taken on an existential urgency shortly before he travelled to Paris. The proximate cause was a seemingly unremarkable walk through the Alexandrovsky Gardens in Moscow after a mathematical meeting at the university. Turning on to the garden path Luzin encountered a rank of young prostitutes 'shivering in the cold' waiting in vain 'for dinner purchased with horror'. The vision of such absolute wretchedness made it impossible to be 'satisfied any more with analytic functions and Taylor series' and, as it worked on his mind over the following weeks and months, threatened him with total breakdown and madness. In the same letter he describes how this experience had simultaneously shattered the materialistic worldview that he had unconsciously absorbed as a student:

Life is painfully depressing for me Pyotr Afanasyevich! The worldviews that I have known up to now (materialist worldviews) absolutely do not satisfy me. I may be wrong, but I believe there is some kind of vicious circle in all of them, some fatal reluctance to accept the contingency of matter, some reluctance, which I find absolutely incomprehensible, to sort out the fundamentals, the principles. I have only recently come to understand this. I used to believe in materialism, but I was not able to live according to it, and was miserable, infinitely miserable […] At the moment my scholarly interests are in principles, symbolic logic, and set theory. But I cannot live by science alone… I have nothing…

The ever-present risk run by the materialist is that one day he may be forced to take his materialism seriously. It is a strange quirk of human psychology that we can annihilate the world in theory, but go on living in it quite happily, as if it were of no real consequence to our lives. But this is at best an unstable equilibrium, and the smallest perturbation can throw it into chaos. That is what happened to Luzin. The face of the girl shivering in the Moscow streets had struck him like that of the blind beggar in Wordsworth's Prelude; it was as if he had been 'admonished from another world'. And there was no way to translate this experience into the language of materialism.

What finally liberated Luzin from the vicious circles of materialistic philosophy was reading an early manuscript version of Florensky's The Pillar and the Ground of Truth, which had been given to him in 1908, six years before its final publication. As he put it to his wife in a letter on 29 June 1908 'As I read it, I was STUNNED the entire time by blows from a battering ram against a stronghold'. It takes little effort to imagine Luzin reading the second letter on 'Doubt', with its description of the mind's descent through the levels of scepticism, and feeling a thrill of recognition:

'I do not have truth but the idea of truth burns me. I do not have the evidence to affirm that there is Truth in general and that I will attain this Truth. By making such an affirmation I would renounce the thirst for the absolute, because I would accept something unproven… [but] it is also uncertain whether I do yearn for Truth. Perhaps that too only seems. But perhaps this very seeming is not just seeming? In asking myself this last question, I enter into the last circle of the sceptical hell, into the place where the very meaning of words is lost. Words cease to be fixed; they fly out of their nests. Everything turns into everything else… Here the mind loses itself, is lost in a formless, chaotic abyss. Here delirium and senselessness lurk.'

P Florensky, The Pillar and the Ground of Truth, trans. B Jakim, Princeton University Press, p.30

This is not the place to attempt even a cursory survey of The Pillar and the Ground of Truth, but Luzin's own summary of Florensky's basic argument is admirably clear - the value of the work lies in the way it 'deals with the most fundamental questions of life, not by taking anything on faith, but on the contrary, by showing the limits of the mind, and then, going beyond them, logically, intuitively, but based on reason'. It may be the single greatest work of philosophical theology written in the last century. Luzin likened it to a pioneer building bridges over separated territories, a work which once completed 'will bring a wholeness to everything'.

Luzin survived his terrible interior trial; and by some miracle of providence he was passed over by the authorities when Kolman tried to destroy him. Florensky would ultimately share the same fate as Egorov. Exiled in 1928, he was later granted permission to return to Moscow around 1930, only to be arrested on confected charges of attempted sedition. He was subsequently sentenced to a decade of hard labour, first on the Baikal Amur Mainline which was then under construction, before being moved to Solovki and finally brought for further investigation to St Peterburg. Without ever facing public trial he was sentenced to death, supposedly for concealing the whereabouts of one of Saint Sergius' relics, and executed somewhere near St Petersburg on a winter's night in 1937.

Luzin’s crisis reminds me of an atheist materialist friend of mind who felt like he went through crises of “unbelief” like a shadow of how the believer would go through a crisis of faith.