In my last blog I made a big deal out of the following passage, taken from Kenneth Boulding’s 1968 address to the American Economic Association (AEA), arguing that the first sentence concerning the difference between 'knowledge' and 'control' constituted a 'killing blow' for Lionel Robbins' otherwise attractive vision of a 'value-free' economics:

We cannot escape the proposition that as science moves from pure knowledge toward control, that is, toward creating what it knows, what it creates becomes a problem of ethical choice, and will depend upon the common values of the societies in which the scientific subculture is embedded, as well as of the scientific sub-culture. Under these circumstances science cannot proceed at all without at least an implicit ethic, that is, a subculture with appropriate common values.

Kenneth Boulding, 'Economics as a Moral Science' (1968)

I want to come good on the promise I made in that blog to think a little bit more about the second part of this quotation, concerning the 'values of the scientific subculture'. Boulding's own attempt to develop this point is unsatisfactory, and so this can be thought of as an attempt to patch up his arguments.

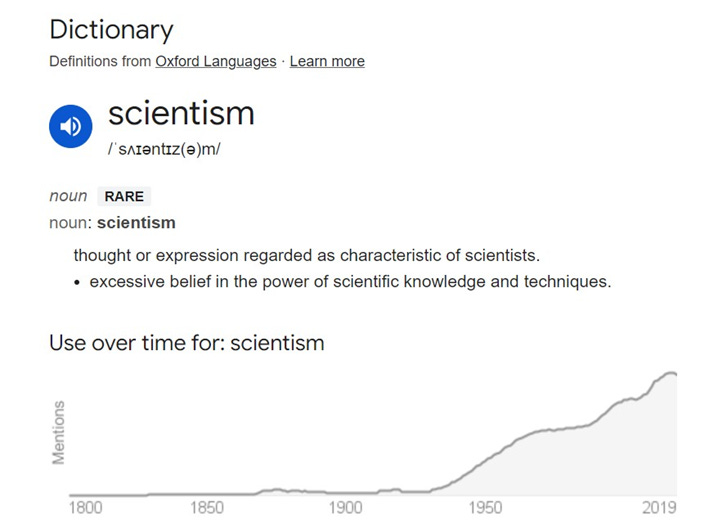

Boulding lacked a bit of terminology for what he was trying to describe in talking about the values of the 'scientific subculture', which today we would call 'scientism'. A quick glance at the Google Books Ngram viewer (below) for the incidence of scientism shows that the word only really started to take off around the time that Boulding was writing his address, and given his tendency to favour elegant archaisms over contemporary jargon, it is hardly surprising he does not use the word. Apart from anything it is an ugly word, and as it has been used largely as a polemical device, it is also unstable, in the sense that it lacks an agreed definition.

Interestingly, only three years after Boulding's paper was read at the AEA, the legendary mathematician Alexandre Grothendieck made his own attempt to analyse and critique scientism in a trenchant little essay entitled 'The New Universal Church' (1971). For those not familiar with Grothendieck's life story, he was for a time one of the most important figures in European science, as the founder of the Institut des Hautes Études Scientifiques (IHES), in Bures-sur-Yvette, and the driving force behind a research program in algebraic topology and geometry that helped resolve the Weil conjectures. Then in 1970 he abandoned the IHES, citing the stifling spiritual atmosphere of the mathematical research community, and took himself away to the Pyrenees where he analysed his own dreams and wrote long tracts about the decay of values and the need for moral and religious renewal.

Between leaving the IHES and going into seclusion, he published the paper on scientism which, to my mind, contains probably the most simple and elegant definition of scientism conceivable:

'The experimental-deductive method, spectacularly successful for four hundred years, has had a continually increasing impact on social and daily life and a corresponding increase (until recently) in its prestige. At the same time, through a process of “imperialist expansion", which needs precise analysis, science has generated an ideology of its own. We may call this scientism.'

Alexandre Grothendieck, 'The New Universal Church', Editorial from Survivre et Vivre no. 9, pp. 1-8, translated by John Bell

'Science has generated an ideology of its own' is everything Boulding was trying to say, only clearer and deeper, and more suggestive. 'The New Universal Church' is irresistibly quotable, even if we can't give up the nagging sense that we are putting ourselves in the way of a powerful rhetorical current that could drag us off into strange places:

'Science is taught dogmatically, as revealed truth. Accordingly, the power that the term "science" exercises over the minds of the general public has a quasi-mystical and irrational nature. For the general public, and many scientists as well, science is like a kind of black magic, and its authority is at once indisputable and incomprehensible […] it is the only religion which has the arrogance to assert that it is based not on myth, but on Reason alone, and to present as "tolerance" the particular blend of intolerance and amorality that it fosters.'

Alexandre Grothendieck, 'The New Universal Church', Editorial from Survivre et Vivre no. 9, pp. 1-8, translated by John Bell

As the title of the essay suggests, Grothendieck goes on to fully work out the analogy between scientism and religion (Grothendieck was profoundly religious but had a mistrust of its social forms), talking about how scientists have readily assumed the roles of 'priest and high priests' and how this creates a power structure that is as formidable as any church seen in history. There are enjoyable digs at, among others, Eugene Rabinovitch and Jacques Monod (the latter produced basically a 'gospel' of scientism in his La Hasard et la Necessite). Grothendieck concludes by offering a sketch of what he calls the 'Credo of Scientism', a summary of the 'principal tendencies' of the scientistic ideology. Here is a compressed version of it:

The Credo of Scientism

Myth 1: Only scientific knowledge is true or real knowledge; that is, only knowledge which can be expressed quantitatively, or formalized, or repeated at will under laboratory conditions, can be the content of true knowledge. Feelings and experiences such as love, emotion, beauty are not knowledge, at least insofar as they are not subsumed under a scientific theory. Insofar as ethics is an object of knowledge, it can be investigated by scientific methods: it follows that science becomes the foundation of ethics.

Myth 2: Whatever can be expressed in quantitative terms, or can be repeated under laboratory conditions, is an object of scientific knowledge and ipso facto valid and acceptable. In other words, truth (with its traditional value content) is identical with knowledge, that is, with scientific knowledge.

Myth 3: The “mechanistic" or “formalistic" or “analytic" view of nature also known as 'Science's dream' – roughly, the sum total of reality, including human experience and relationships, social and political forces and events, will be expressible in terms of systems of elementary particles. Ultimately, the world will become nothing more than a particular structure within mathematics. The notion of purpose can have no place in such a world view and, as the basic physical laws can now be expressed in statistical form, the mechanist can transcend the strictly determinist conception of nature, and in principle subsume the idea of free will as well.

Myth 4: The role of the expert. Knowledge, both for its development and its dissemination through teaching must be split into many fragments or special fields. Only the opinion of the experts in a given field has any bearing on any question in this field. This furnishes the foundation for the power of the expert deriving from the incapacity of any person outside his speciality to understand him. It also justifies the following (rarely formulated) consequence, namely, that nobody whatsoever can claim to have valid knowledge about any complex part of reality.

Myth 5: Science and the technology derived from science, and they alone, will solve mankind's problems.

Myth 6: The experts alone are qualified to make decisions, as only the experts “know". Within the sphere of social and political decisions, reality is too complex for a single expert to be truly competent. This difficulty is resolved in practice by introducing another sort of expert, the “decision-making" expert.

Having warned of the powerful rhetorical force of Grothendieck's essay, I should probably put my cards on the table and say that I am basically in agreement with all of it. The only thing I want to add is to develop a point that Grothendieck makes under the rubric of myth 1 – that scientism's absolute claim to universal knowledge demands the creation of a purely scientific ethic (which brings us back to Boulding). There have been recent popular attempts to establish such an ethic, but they always stray beyond the resources of science itself, and so invalidate themselves. I have seen only one statement that gets close to a pure scientific morality, and it can be found in Robert Jungk's book Brighter than a Thousand Suns (1956), a history of the Manhattan Project, where he quotes Robert Oppenheimer in 1949, reflecting on his difficulties with the General Advisory Committee:

'I do not think we want to argue technical questions here and I do not think it is very meaningful for me to speculate as to how we would have responded had the technical picture at that time been more as it was later. However, it is my judgment in these things that when you see something that is technically sweet you go ahead and do it and you argue about that to do about it only after you have had your technical success.'

Robert Jungk, Brighter Than a Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists, trans J Cleugh,p.226

If it's technically sweet, do it – that is the categorical imperative of the pure science-ethic.