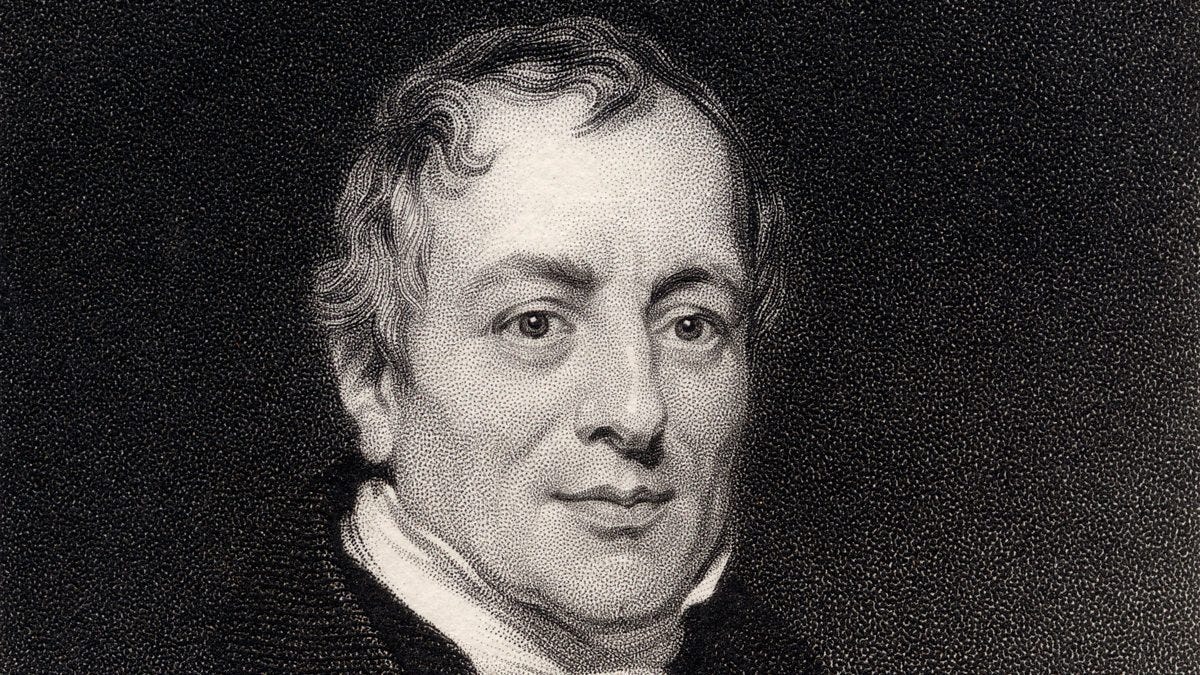

There is a new book out that revives an old libel against David Ricardo, first imputed to him by Joseph Schumpeter, that he was the initiator of the great divorce between economics and reality. It is called Ricardo's Dream: How Economists Forgot the Real World (2024) by Nat Dyer, and it is doing well-enough on Amazon that I feel less reluctant than I usually would to provide some 'negative feedback'.

I have not read the whole book (so apply suitable adjustments when you think about purchasing it), but from the statement of its argument in the first chapter it is largely a defence of the following passage from Schumpeter's History of Economic Analysis (1954), where we first find the description of so-called 'Ricardian Vice':

[Ricardo's] interest was in the clear-cut result of direct, practical significance. In order to get this he cut that general system, to pieces, bundled up as large parts of its as possible, and put them in cold storage - so that as many things as possible should be frozen and 'given'. He then piled one simplifying assumption upon another until, having really settled everything by these assumptions, he was left with only a few aggregative variables between which, given these assumptions, he set up simple one-way relations so that, in the end, the desired results emerged almost as tautologies… the habit of applying results of this character to the solution of practical problems we shall call the Ricardian Vice'

To borrow from Leonard Savage, you succumb to Ricardian vice when you make a 'small world' model, where probabilities can be assigned to all contingencies and variables switched on and off by fiat, and apply it to a 'large world' where everything is uncertain and ambiguous. Economic systems are very large worlds, and much of the difficulty of doing economics comes from trying to identify parts of those systems which can be safely assumed away. Dyer is probably right to say that Ricardian Vice, so construed, is the cardinal sin of modern economics. The history of economics is littered with ruined models that have been broken by a sudden and shattering run-in with reality.

But is it true to say that the method of naively piling up 'simplifying assumptions' and then crudely mapping them onto the real world came from Ricardo? I have my doubts. To start with, take up your copy of The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, leaf some way through chapter VI, and at the bottom of a section of trivial arithmetic on the variance in labour costs under different assumptions, you will find the following statement:

'In all these calculations I have been desirous only to elucidate the principle, and it is scarcely necessary to observe that my whole basis is assumed at random, and merely for the purpose of exemplification. The results, though different in degree, would have been the same in principle…'

Yes, there are simplifications in Ricardo but they are not made under the influence of a peculiar intellectual malady that has clouded his mind. On the contrary, Ricardo is utterly deliberate and meticulous in presenting his assumptions as assumptions, which he can then adjust or relax as appropriate. As he put it in the ‘Reply to Mr Bosanquet’ the main function of theory is to create a ‘standard of reference’ which will allow men to ‘sift their facts’. Creating such a standard always involves simplification; without these abstractions we are left ‘credulous, and necessarily so’.

One economist who gets tangled up in Dyer's history of Ricardian vice is Paul Samuelson. According to Dyer, Samuelson though more careful than Ricardo in the way he handled his models, was, nonetheless, responsible for 'turning the tide in economics back to unreality'. I find this rather curious as Samuelson was one of the few major economists who actually avoided the vice of naively confusing his models with the world. That, at least, is the view of Robert Solow, who said of Samuelson that he always worked with two models at the same time, the clean and mathematically self-consistent one that was put down on paper and the one 'in his head' (i.e. the model where the vagueness and fuzzy edges are allowed back in). This strikes me as very close to the way Ricardo worked as well; his models were speculative instruments rather than strict descriptions of the world as it is in itself.

The other thing that unites Ricardo and Samuelson is the fact that they both made vast fortunes trading securities. At the time of his retirement, according to The Morning Chronicle obituary note, Ricardo was worth upwards of half a million pounds, having 'hardly ever sustained a loss'. As for Samuelson, in the late 1960s he went into business with Helmuth Weymar, who would set up Commodities Corporation, a commodities and futures fund that was eventually acquired by Goldman Sachs for $100m in 1997. There are few other serious economists who have been so successful in allocating capital, something that is very difficult to do if you do not have a firm grasp on the real world. Incidentally, as we are on the subject, the only other person I can think of is Piero Sraffa, the preeminent Ricardian of the twentieth century, who, according to a wonderful reconstruction of his trading activities by Irwin Union, managed to accumulate some 120kg of Gold bullion by the final decade of his life following the purchase of Imperial Japanese Government bonds on the London Stock Exchange during the second world war.

But there is surely something true in what Dyer says about the way economics got lost in theoretical abstractions. If it has to come down to one particular economist, I think a better candidate would have been Leon Walras, whom Schumpeter regarded as 'the greatest of all economists'. Contrast the following passage on Walras with what Schumpeter had to say about poor Ricardo:

[Walras'] system of economic equilibrium, uniting, as it does, the quality of ‘revolutionary’ creativeness with the quality of classic synthesis, is the only work by an economist that will stand comparison with the achievements of theoretical physics.... It is the outstanding landmark on the road that economics travels toward the status of a rigorous or exact science and, though outmoded by now, still stands at the back of much of the best theoretical work of our time.

And yet, has there ever been an economist who could be accused of indulging in pilling up simplifying assumptions as readily as Walras? Don't take my word for it, just read the following letter Henri Poincare wrote to Walras in 1901, after the latter asked the former to check his maths:

What I had in mind was that every mathematical speculation begins with hypotheses, and that if such speculation is to be fruitful, it is necessary (as in applications to physics) that one be aware of these hypotheses. If one forgets this condition, one oversteps the proper limits. For example, in mechanics one often neglects friction and assumes the bodies to be infinitely smooth. You, on your side, regard men as infinitely self-seeking ['egoistes'] and infinitely clairvoyant. The first hypothesis can be admitted as a first approximation, but the second hypothesis calls, perhaps, for some reservations.’

Infinitely self-seeking and infinitely clairvoyant agents are the kind of assumptions that were the true cause of the very real 'divorce' mentioned above, and there is an interesting story to tell about how we go from the early Walrasian model of general equilibrium to the mathematical reveries of Arrow and Debreu, where the 'real world' vanishes altogether (this has been done rather splendidly by Bruna Ingrao and Giorgio Israel). So why not call this particular sin by a more appropriate name - Walrasian vice?

In truth there have been two vices attributed to Ricardo, one intellectual (originating in Schumpeter) and one moral. In his enjoyable, influential, but often inaccurate, popular polemic The Affluent Society (1954), John Kenneth Galbraith picked out Ricardo and his close friend Thomas Malthus as the two primary sources of what he calls the 'tradition of despair' in economics. The impression we are given in Galbraith’s beautifully turned prose is of two highly intelligent ghouls who were unperturbed by human suffering and degradation, and accommodated these horrors to their economic systems. It was his inherent pessimism that led Ricardo to his characteristic positions on the population question, diminishing agricultural returns, the declining rate of profit and the fixity of real wages around the point of mere subsistence, not the other way around. The insinuation made by Galbraith is that the supposed brutalities of the Ricardian (or the Malthusian) model are reflections of the brutality of its author's mind.

I would ask you to contrast this with the final words Ricardo sent to Malthus before he died, in a letter dated 31 August 1823:

And now, my dear Malthus, I have done. Like other disputants, after much discussion we each retain our own opinions. These discussions, however, never influence our friendship; I should not like you more than I do if you agreed in opinion with me.

Pray give Mrs. Ricardo's and my kind regards to Mrs. Malthus.

Yours truly,

David Ricardo.

We rarely hear anyone in public life speak like this anymore. It is all sound, fury, hysteria and mutual recrimination. After learning of his friend's untimely death Malthus wrote that 'Our interchange of opinions was so unreserved, and the object after which we were both enquiring was so entirely the truth and nothing else'. To get to the truth requires argument, and to argue well requires civility. We desperately need to re-learn this Ricardian virtue if we hope to get out of the twenty-first century intact.